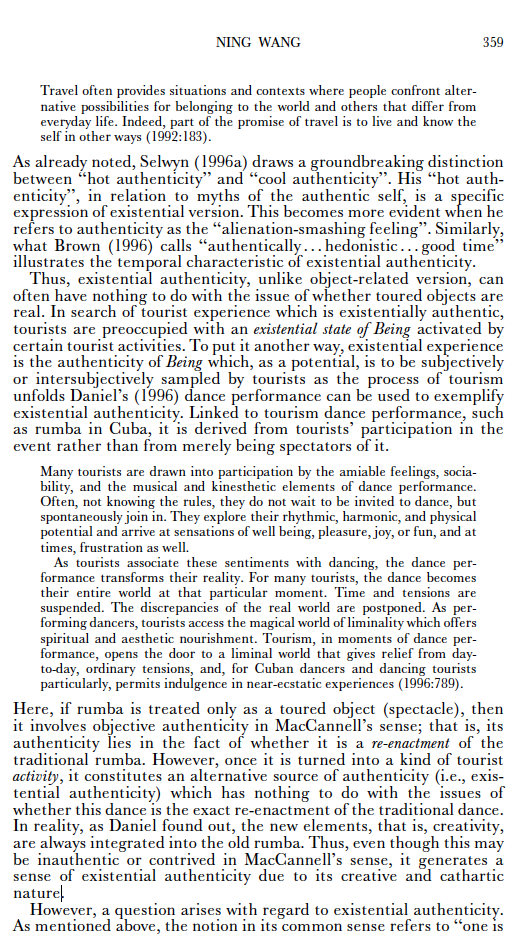

Three Korean nationals wear the (now trendy) hanbok in Insadong, Seoul, which is a prime "arena of the authentic" in Korea, where the hanbok has long been a semiotic marker for Korean Tradition. In a Society of the Spectacle, even the Traditional has become just another referent in a sea of symbols that have become equivocated into meaninglessness, and just another element to be recycled into the relentless, all-consuming maw of the Trend Machine.

Ning Wang (1999) provides a lot of the theoretical undergirding for this paper in his explication of what he calls "existential authenticity" in tourism studies. In observing and interacting with young subjects as a street photographer in Seoul, I have increasingly come into contact with seemingly Korean subjects around popular tourist sites who turn out to be Chinese nationals who are merely in Korean dress.

Unlike traditional Chinese tourists who seem content to sightsee the city of Seoul as a site of many toured objects, there is a sizeable number of tourists from China who actively engage in the much more participatory act of finding trendy Korean clothing, wearing them, and experiencing Korea as an apparent Korean. The act of passing -- no matter how superficially -- as a Korean seems to add quite a bit of existential authenticity to the tourism experience in Korea. Initial conversations with several subjects has yielded the existence of an industry dedicated to providing Chinese tourists with this experience of passing through Korea as a Korean.

Wang, N. (1999). "RETHINKING AUTHENTICITY IN TOURISM EXPERIENCE." Annals of Tourism Research 26(2): 349-370.

Background to the Study, from a Stunning Realization

I initially stumbled across the phenomenon of Chinese tourists “passing” as Korean locals as a street photographer shooting a story for the Huffington Post’s Style section, a story on the styles of the 2015 summer focusing on Ewha Women’s University in Seoul as a representative site of young female sartorial consumption. As an investigator and photographer, my goal was to identify the most common (frequently occurring) and representative examples of Korean summer 2015 fashions of the Seoul streets for the story. With my team of assistants/intern/students, we selected a young woman in an American football jersey dress who seemed the absolute epitome of that style of the time.

However, I was surprised to learn from our short interaction in Korean that not only was she a Chinese national but that she was on a short trip for shopping, and was wearing the dress, shoes, and other items she had bought on the very trip she was on. It was, however, our very next subject, who brought about the moment of realization that was the impetus for the writing of the present article.

On the same day and search for photographic subjects, we encountered two seemingly Korean young women dressed in matching trend items of the day, two sports jersey-style tops and a mass market approximation of the homemade “Daisy Duke” extremely short pants, made in the style of jean pants cut into shortsso short that the pockets extend below the home-hewn hemline, or alternatively, rolled up that short.

From "Existential" to "Performative" Authenticity

And upgrade from "existential authenticity" -- "performative authenticity": an integrated notion that draws heavily on Judith Butler’s notion of identity performance, and Bourdieu’s field theory and habitus, and conveys the “transposition of objective structures of the field into subjective practice of the individuals.”(Zhu)

This Is Where It Gets Queer

This is where I take a sharp departure into the seemingly unusual theoretical toolbox of psychology and what is now called queer studies. Important to the notion of “performative authenticity” is where the performance of particular acts imbued with identity-relevant symbolic meaning are the points through which individuals can reach — and actively maintain — a state of “existential authenticity”. It must be achieved and maintained through performative acts. In this sense, I argue that there is a hugely useful theoretical parallel between male-to-female transvestism and cosplay.

Magnus Hirschfeld is the legendary physician/sexologistwho was a “key player in the development of taxonomies of sexual identities and who coined the terms “transvestite” and “transsexual.” This is where Hirschfeld’s data becomes useful as a parallel case of “performative authenticity”, where queer theory can combine with Butlerian critical theory and lead us to some useful insights regarding the question of dress and the performance of imagined identities. In this sense, the cases aren’t all that different (Chinese or even modern Koreans wearing a hanbok, cosplay, and transvestism) and stand in a relationship of useful parallel. So, it's time to talk about sex -- very queer sex -- as a performative act that defines a state of being.

This is where we get to the meat of the matter. Prior to the work of Magnus Hirschfeld, Freudian psychology was too focused on "fetish" as the way of explaining (largely male) crossdressing; it was supposedly an act related to the sexual excitement had in response to an object that itself was imbibed with special sexual meaning due to its symbolic associations with the person it represented (often a mother, lover, or other object of sublimated sexual desire). But Hirschfeld had a different insight. He held that his largely "heterosexual" male interviewees didn't express symbolic, fetishistic desire to touch, wear, or masturbate upon certain physical objects (which were usually items of women's clothing), but they were actually objects that enabled fleeting yet intense moments of being women. Importantly, these were usually "women" in some idealized, fantasy form (an innocent child, prostitute, or respectable Lady) and often such women as engaged in fantastical moments of extreme being female in the context of hypersexualized, often pornographic notions of femininity, such as being forced into prostitution or being raped. Besides these fleeting instants of femininity, most men describing such sexually motivated feelings of authenticity as women emphasize their extreme distaste (or disgust at) for the idea of having sex with a man as a man. It is apparent that the pleasure in sexual congress comes from the pleasure in achieving authenticity as a woman through the performance of womanness as defined through clothing, as opposed to the sexual acts themselves.

If the achievement of authenticity and the pleasure in passing is not something that is easy to maintain as a passive, static state, but is instead something that requires continuous effort though the constant performance of meaningful acts that actively define that existential state of being is something that nominally heterosexual male crossdressers do through clothing, the parallel to another situation in which sartorial practices define the achievement and maintenance of a state of pleasurable passing as defined through performativity -- Chinese tourists in Korea passing as Korean -- becomes clear. My own ethnographic interactions and interviews suggest this is a major factor in why and how Chinese tourists come to Korea.

Koreans, Tradition, and Arenas of the Authentic

It occurs to me that not only is there a well-defined notion of the Authentic in korean contemporary culture -- usually defined as things associated with a constructed notion of "Tradition" in Korea and with their many sartorial, fetish markers -- but there are actual arenas of the Authentic. These are geographic areas in Korea that are metonyms of the Traditional, such as Gyeongbuk Palace in Seoul. It is my argument that this explains the recent huge uptick in the sartorial practice of wearing hanbok in the vicinity of as well as inside traditional structures. In a tourist economy in which where natives and tourists are both engaged in a struggle to achieve a pleasure in performing an imagines Authentic (whether that be defined as a mere Korean or more ideally, a Traditional Korean), this points to a multi-layered kind of phenomenon involving objectivist notions of the authentic articulated somewhat separately from the concerns of the constructivist/existentialist notions of the authentic. But what about when the “arenas of authenticity" are increasingly occupied by natives engaging in the same performative practices as the tourists? It would be unusual to see this unless there were two levels of authenticity here, no?

Two Chinese tourists "perform" Korean Tradition in the ultimate arena of Authenticity, the souvenir shop.

Two Korean visitors to the Gyeongbok Palace "perform" Korean Tradition in the ultimate arena of Authenticity, the “souvenir shop” of national tourist sites.

In the midst of a “culture industry”-dominated society that has succeeded in commodifying culture as a major part of the economy, it makes sense that the natives take pleasure in consuming it, although the nature of the performative authenticity — the basis of authenticity itself — may be vastly different. But the forms of performing authenticity look largely the same, as do the end goals of achieving a state of existential authenticity. This is where what is now called “queer” identity, tourism studies, and visual sociology can come together …especially when these young women,from inside and outside Korea, are engaging in the same performative sartorial practices…

In a situation in which both natives and tourists are both engaging in performative authenticity within arenas of authenticity, really, who is impersonating whom, and which is any more "real" than than the other? Or, alternatively, is the Korean doing Traditional Korea any less other than the Other?

Working Bibliography

Asphodel, Autumn. "Passing as Female | Male to Female Transgender / Transsexual" (YouTube Video). 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XLTcwqfDKXE.

Hill, Darryl B. "Sexuality and Gender in Hirschfeld’s Die Transvestiten : A Case of the "Elusive Evidence of the Ordinary" " Journal of the History of Sexuality 14, no. 3, July (2005): 316-32.

Wang, N. (1999). "RETHINKING AUTHENTICITY IN TOURISM EXPERIENCE." Annals of Tourism Research 26(2): 349-370.

Zhu, Yujie. "Performing Heritage: Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism." Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012): 1495-513. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.04.003.